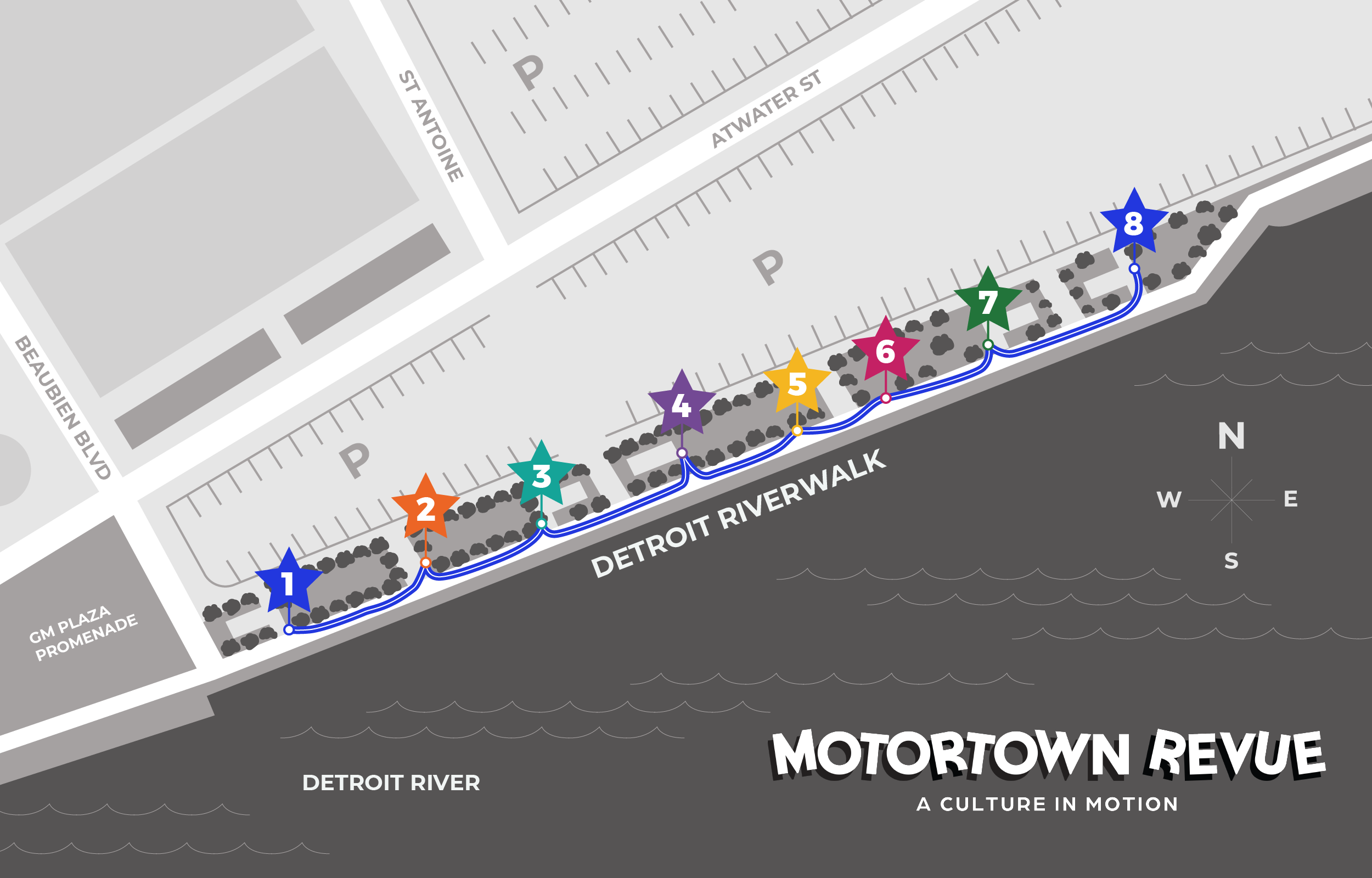

Sign 1

Culture in Motion

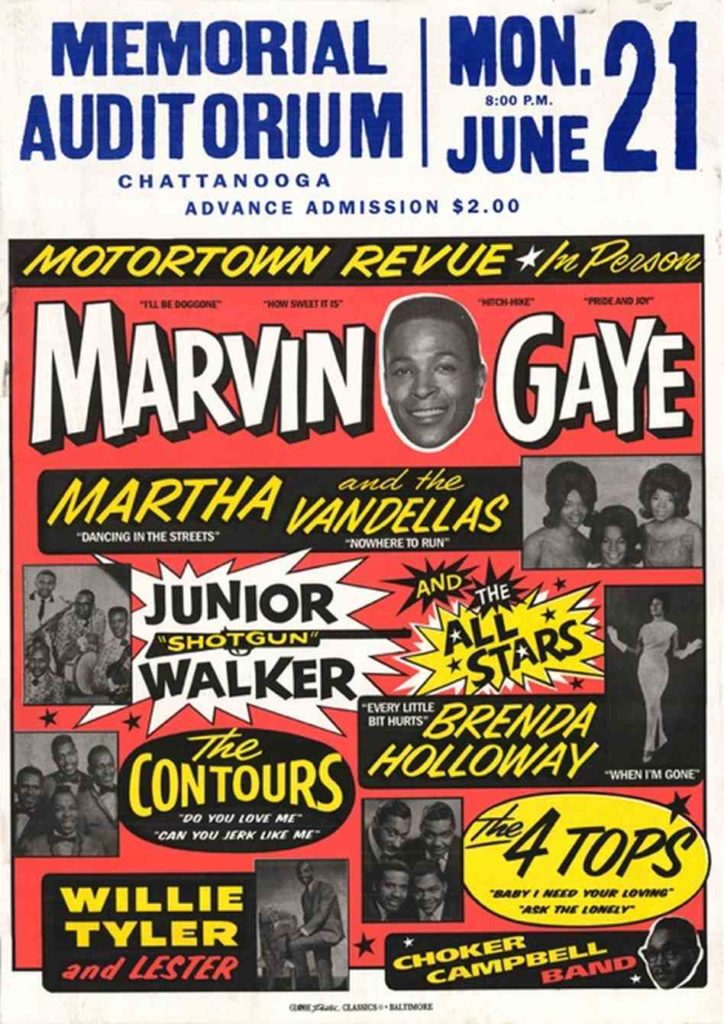

A poster advertising a Motortown Revue concert in Chattanooga, Tennessee on June 21, 1965.

Sixty years ago, in October 1962, Motown’s roster of young singers, musicians, and staff boarded a crowded bus that would carry them for the next three months as they performed more than fifty one-nighters in towns across the United States. In an era of racial division, the African American artists faced discrimination as they performed to integrated and segregated crowds in the North and South. Teenagers pressed their way to the venues, standing in lines that wrapped around buildings, anxiously waiting to see their musical idols.

The Supremes perform at the Apollo Theater in New York City, 1963.

Little Stevie Wonder performs onstage, 1963.

For as little as $1, audiences could see eleven Motown acts perform live.

The Motortown Revue became an annual event that even crossed the Atlantic Ocean to tour Europe. The shows introduced new audiences to the Motown Sound and boosted the careers of up-and-coming artists including Little Stevie Wonder, Marvin Gaye, Mary Wells, The Marvelettes, The Supremes, Martha & The Vandellas, The Contours, The Four Tops, Kim Weston, Gladys Knight & The Pips, The Temptations, and many others.

“The plan behind the Motown Revue was to send all of the label’s biggest recording stars and young hopefuls out on the road to promote our latest recordings, turn those recordings into hits, and return as ‘stars.’”

-Martha Reeves

Sign 2

The Road to Success

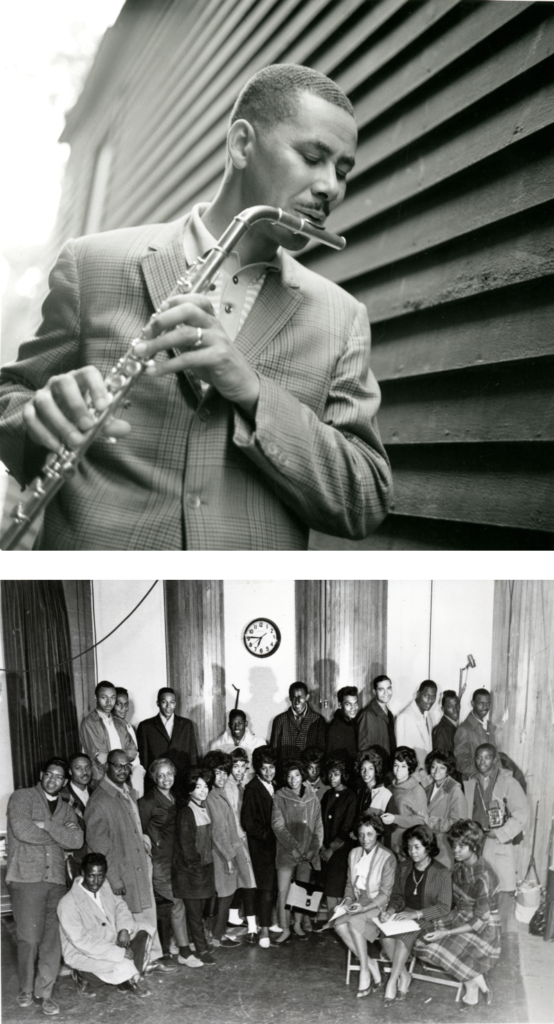

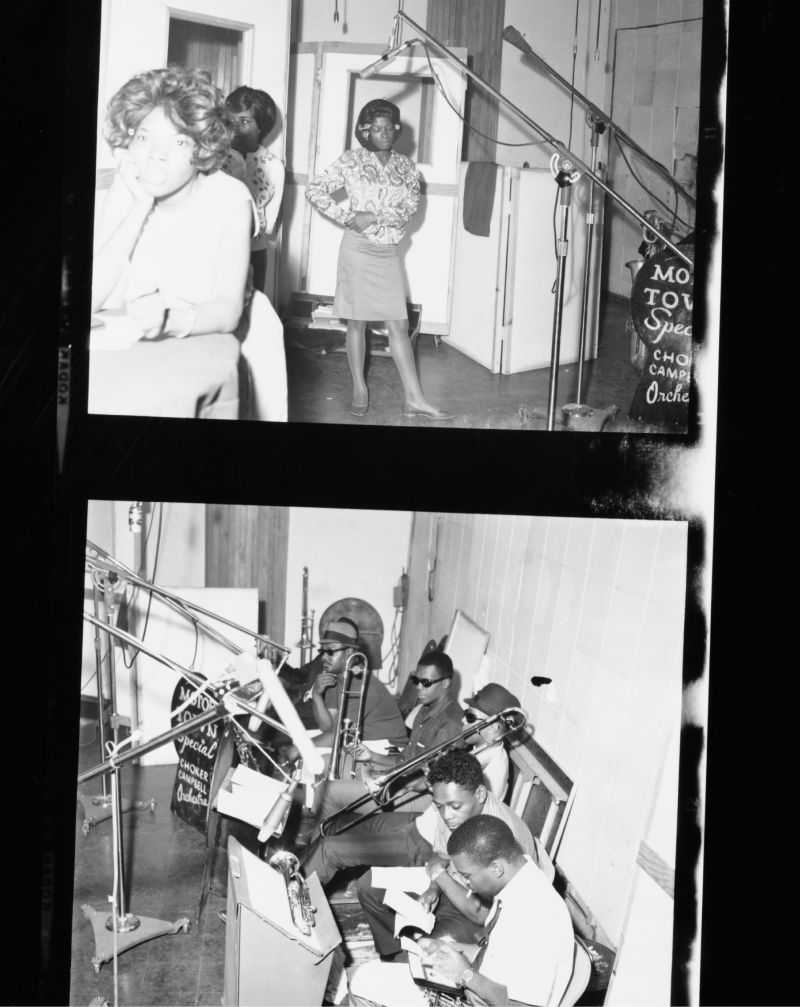

Thomas “Beans” Bowles was a gifted jazz musician and skilled manager who conceived the idea for the Motortown Revue. He acted as lead road manager during the first tour (Top).

Motown artists, musicians, chaperones, and administrative staff gather for a group photo before the Motortown Special, 1962 (Bottom).

Berry Gordy founded Motown Records in 1959 with the vision of creating music for all. Just three years later, in 1962, Motown’s acts stood on stage at the Apollo Theater in New York City, in the shadows of the greats, like James Brown and Sammy Davis Jr.

In the early 1960s, the music industry was racially segregated. African American singers performed on the “Chitlin’ Circuit”—the select venues throughout the country that welcomed them. The Apollo was the most prestigious on the Circuit. If you could make it at the Apollo, you could make it anywhere.

Through live performances, Motown could bypass gatekeepers like radio DJs, record shop salesmen, and television hosts who refused to play “race music” to mainstream audiences. For decades, performers often traveled together across the country in “packaged tours” coordinated by white promoters. As demand increased for Motown’s top acts, Motown decided to organize its own packaged tour to reach more diverse audiences.

Esther Gordy Edwards, sister to Berry Gordy, was a Senior Vice President and artist manager. She oversaw the logistics of the tour from headquarters in Detroit.

As Berry Gordy noted, “We realized, we could put our own show on the road… We had in-house everything: artists, producers, musicians, chaperones, and road managers.” Motown sent the sound of Detroit to America, refining the packaged tour model in the process. In short, Motown paved its own road to success.

Sign 3

Gearing Up

Despite the ambitious plan, Motown gave the artists little time to prepare for the Motortown Revue. Joe Billingslea of The Contours recalled that the singers’ recording sessions and local performances doubled as rehearsals, and the groups refined their stage acts throughout the tour. To pull their looks together, the artists purchased matching stage uniforms at department stores or coordinated clothes that they already owned. Claudette Robinson, the only girl in The Miracles, remembered sewing dresses with the help of female relatives to coordinate with the guys’ suits.

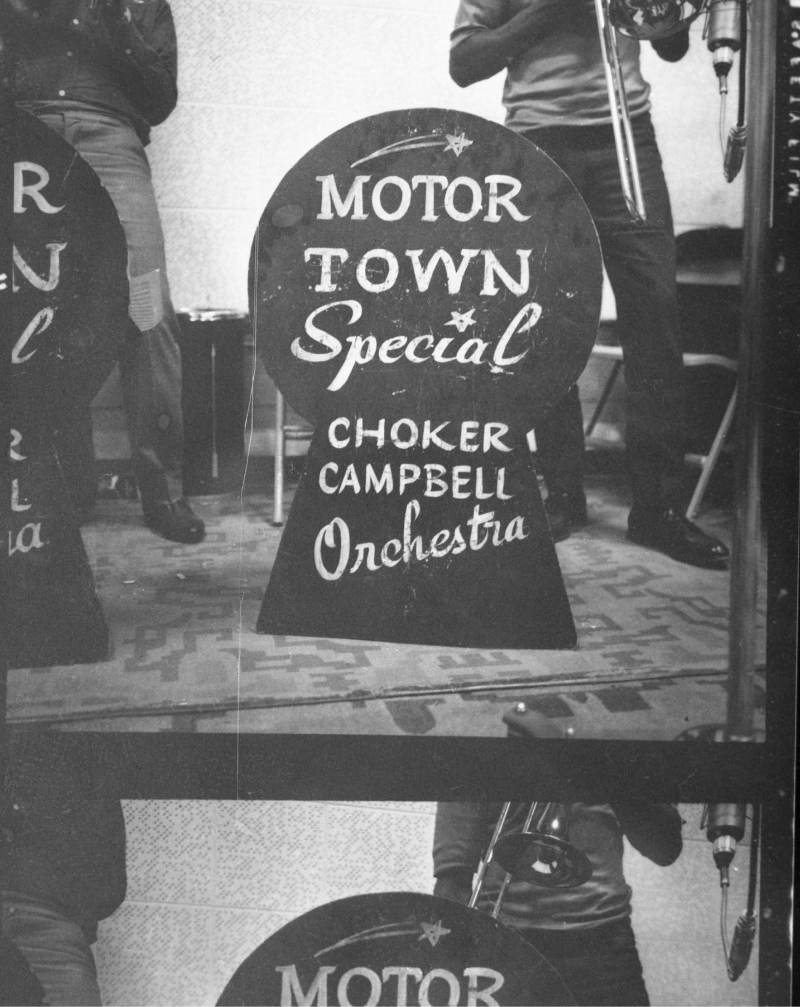

While the artists prepared their acts, Motown coordinated the shows and logistics. The Artists and Repertoire (A&R) Department organized the stage show, from lighting cues to microphone setups. Choker Campbell led a 16-piece band of seasoned jazz musicians who could adapt to spontaneous changes in the show. Back home in Detroit, Motown’s International Talent Management Incorporated negotiated contracts with venues and planned the route.

Customized Motortown Special bandstands created for the tour, 1962.

Motown musicians rehearse for an upcoming show, 1962.

Year after year, Motown’s plans for the Revue got bigger and better. In the mid-1960s, Motown established the Artist Development Department, which taught the young performers poise, stage presence, singing, and choreography. Those vital lessons strengthened their live performances, and the shows became more professional and polished.

Sign 4

Chasing the Dream

“With a twelve-piece band, we were set off on a three-month tour of America—with just three nights in a motel bed. We virtually lived on that one bus, and we always had to sit up because there wasn’t enough room for anybody to stretch out.”

-Martha Reeves

Motown artists board the Motortown Special bus, 1962. Left to right: Mary Wilson (Supremes), Katherine Anderson (Ma rvelettes), Rosalind Ashford (Martha and the Vandellas), Wanda Young (Marvelettes).

During the earliest Motortown Revues, a glamorous lifestyle was a far-off dream for Motown’s artists. Most were teenagers who had never traveled beyond Detroit or Michigan. The Motortown Revue offered a ticket to see the world, but they had to make sacrifices to earn it.

The tour took the artists away from their lives and loved ones for months. After The Marvelettes’ first single “Please Mr. Postman” topped the Pop charts, several members made the difficult decision to dropout of high school to perform full-time. Some artists signed their Motown contracts instead of going to college or starting a steady job in a factory. Others decided to delay getting married or starting a family until after they pursued their dreams. On the road, they kept in touch with people back home by sending postcards or calling from payphones.

A postcard sent by Martha & The Vandellas to Berry Gordy from Louisville, Kentucky, 1962.

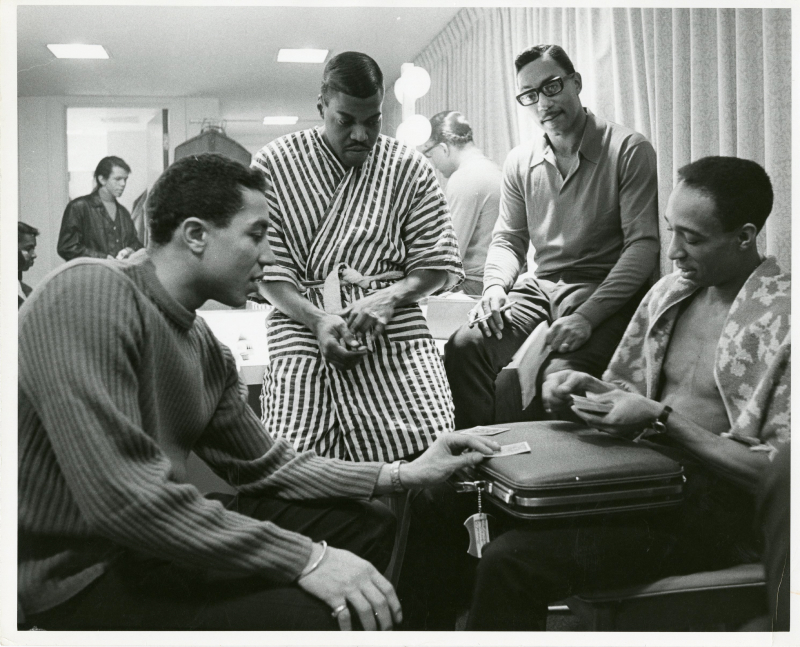

The Miracles play cards in a dressing room. Left to right: Smokey Robinson, Pete Moore, Bobby Rogers, Ronnie White.

The hardships of tour life bonded the artists together. Before cell phones and without a television insight, the Motown crew had to find organic ways to entertain themselves during the long, crowded, and grueling bus rides. In between stops, they could be found playing cards, singing, chatting, playing pranks and name-calling games like “the dozens,” and most importantly, sleeping.

Sign 5

Bridging the Racial Divide

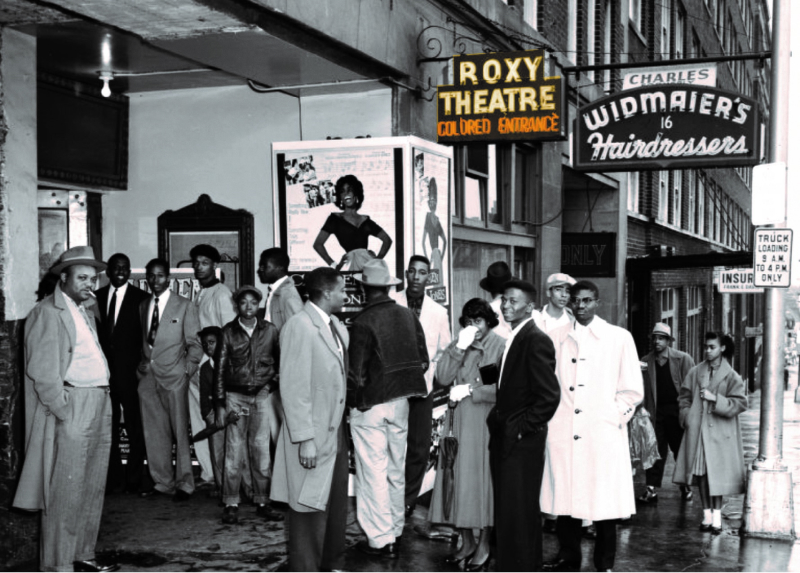

As the artists passed from the North to the South, they encountered increasingly harsh conditions of segregation and discrimination. While African Americans in the 1960s experienced racism in Detroit, it was more overt in the South.

During the tour, when the artists grew hungry or tired, they often found themselves rejected from hotels, restaurants, and even gas stations. While diverse crowds attended the shows, long ropes sometimes divided the auditoriums in half—white people in one section and Black people in another.

“Colored Entrance” at Roxy Theater, Atlanta, Georgia.

In Birmingham, Alabama, after performing for a racially integrated audience, the artists began to load onto their bus. Mary Wilson of The Supremes recalled hearing “several sharp, loud cracks,” which they later discovered were bullets, directed at them. This was not the first or last instance of violence and intimidation aimed at the Motown artists, but it would stick vividly in their memories.

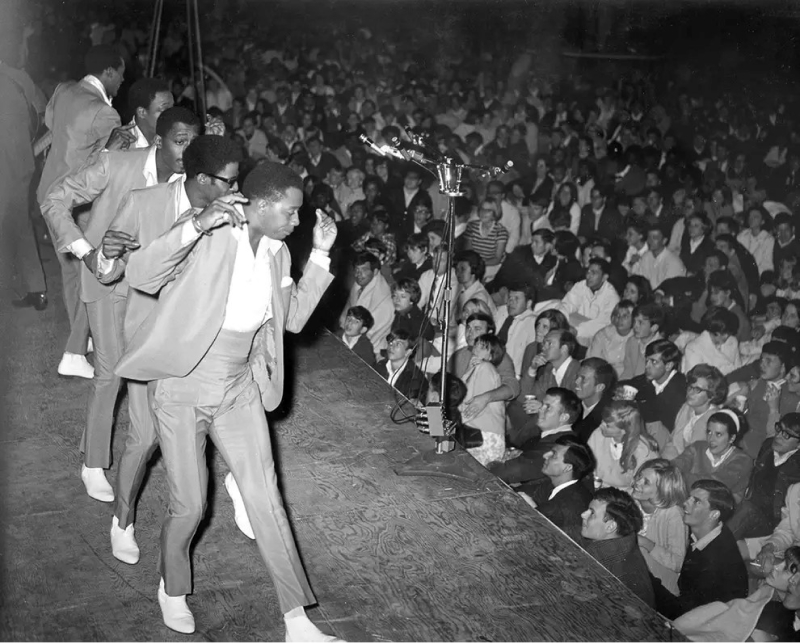

The Temptations show off their tight choreography before a diverse audience.

Despite everything, they soldiered on. The Revue continued to excite crowds while slowly but surely bridging cultural and racial divides. Mary put it best: “Our tours made breakthroughs and helped weaken racial barriers… to see crowds that were integrated—sometimes for the first time in a community—made me realize that Motown truly was the sound of young America.”

Sign 6

The Show Not To Be Missed

Over the years, hundreds of thousands of people attended Motortown Revues. In the mid-1960s Motown adopted the tagline “The Sound of Young America” to reflect its youthful fanbase. Accordingly, teenagers packed auditoriums across the country. They waited for showtime for weeks. The opportunity to see the Miracles perform their hit song “Mickey’s Monkey” live was hard to believe, but seeing Stevie Wonder, The Marvelettes, and Marvin Gaye on the same stage was a dream. They begged their parents to drive them or hopped on a city bus to stand in long lines for hours so they could spend their weekly allowances on two-dollar tickets. Suddenly, they sat in the audience. The excited chatter in the auditorium quieted as the velvet curtain rose and the band began to play.

A diverse group of audience members anxiously wait to see the Supremes in Philadelphia, 1971.

Motown developed many strategies to attract young concertgoers. The company placed advertisements in newspapers, put posters on telephone poles, and recruited local DJs to tell their audiences that the Revue was coming soon. They went directly to Motown’s most devoted fanbase and passed out flyers a local high schools. If all went to plan, crowds would be lined up outside the venue in anticipation of seeing the country’s hottest acts perform live.

Sign 7

Home Sweet Home

After months on the road, the Motortown Revue typically ended at the legendary Fox Theater in Detroit, where it all began. As Martha Reeves said onstage before performing with Martha and the Vandellas,“It’s wonderful being home… the crowds away from home are nothing like these.” Each night felt like a homecoming performance; the crowds already knew and loved the Motown Sound, and friends and family filled the theater.

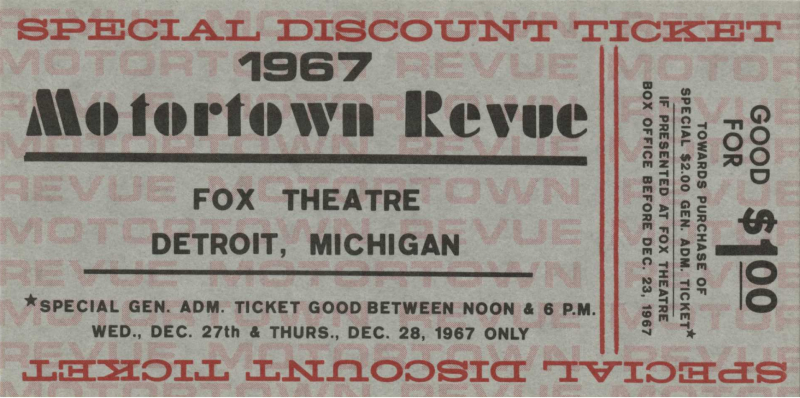

Poster for the 1967 Motortown Revue at the Fox Theater.

By the end of the tour, Motown’s artists had perfected the act. After the Fox Theater curtain rose in1963, host and comedian Bill Murray appeared onstage to welcome the audience, then tossed it to Choker Campbell and his 16-piece band to set the groove. One after another, Motown acts took the stage with their tight vocal harmonies and synchronized dance steps. The crowd went wild. Head lining acts such as The Miracles, Little Stevie Wonder, and Mary Wells performed three or four songs, while lesser-known groups such as The Temptations (who were not yet superstars) performed just two. The night ended with The Miracles performing their hit “Mickey’s Monkey” as all the singers joined them onstage for their signature finale

A coupon for a discounted ticket to a Motortown Revue concert at the Fox Theater in Detroit, 1967.

After the tour, the artists returned to the daily grind. The Revue succeeded in introducing Motown to new fans who were now hungry for more hits. Back at Hitsville, the artists were sent to Studio A to record songs written for them in their absence. Requests for solo performances came in from the cities they’d passed through. Eventually, Motown went international with tours of the United Kingdom and Europe in 1965. Through the Motortown Revue, Motown found its formula for success, achieving the visibility needed to launch the independent label to the top of the national music scene.

Bibliography

Billingslea, Joe. Interview. 2021. By David Ellis. Telephone Interview.

Bowles, Dennis. Dr. Beans Bowles “Fingertips” The Untold Story. First ed., Sho-nuff Productions, 2004

Gordy, Berry. To Be Loved: The Music, the Magic, the Memories of Motown: An Autobiography. 1st ed., Warner Books, 1994.

Helton, Annette. Interview. 2021. By David Ellis. Telephone Interview.

Reeves, Martha, and Mark Bego. Dancing in the Street: Confessions of a Motown Diva. 1st ed., Hyperion, 1994.

Robinson, Claudette. Interview. 2021. By David Ellis. Telephone Interview.

Robinson, Smokey, and David Ritz. Smokey: Inside My Life. 1st ed., McGraw-Hill, 1989.

Taylor, Marc. The Original Marvelettes: Motown’s Mystery Girl Group. Aloiv Publishing Co., 2004

Williams, Otis, and Patricia Romanowksi. Temptations. 1st ed., G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1988.

Wilson, Mary, and Patty Romanowski. Dreamgirl; &, Supreme Faith: My Life as a Supreme. 3rd ed., Cooper Square Press, 1999.